30 November 2020

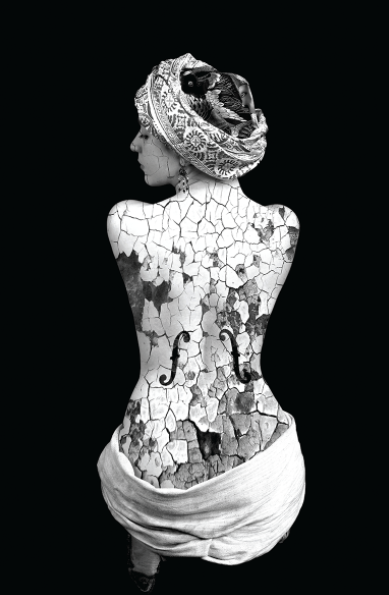

Main image by Philippe Lucchese

When I was a teenager, I remember pretty much the precise moment I learned the real definition of the word “amateur”. It was while watching some or other rugby tournament on the telly. I actually enjoyed watching rugby. It interested me, and I later played for Nottingham University women’s team – badly, I admit. I never fully understood the rules, and I was scared of getting my back, neck, nose or jaw broken, and so played rather tentatively. But I did enjoy the messy, muddy physicality of it all. Football though has never much interested me – I only ever watched the finals, and perhaps the semis – of big tournaments.

I remember being told that Rugby was an “amateur sport”, whereas football was a “professional sport”. I struggled to understand why. Surely the rugby players played rugby well – at least as well as the footballers played football? If not better, in my humble opinion, for surely rugby rules were more complex, the game more physical, more challenging, no?

At that stage, my working definition of the word “amateur” was that it meant “just for fun”, “not very seriously”, “a side interest”. Not to the same standard or level as something “professional”. Later the crucial distinction of “amateur” as meaning “unpaid” came into my understanding, and while I still couldn’t quite figure out why top rugby players were not paid for their skill and representing their countries, I understood the financial distinction between the two words, and that top rugby players had a day job to go to. It didn’t make much sense to me, but did make me all the more admiring of their prowess. It was through the sports world that I grasped the real meaning of the word “amateur” – not as being about level or skill, but as being about whether or not you got any money for your skill.

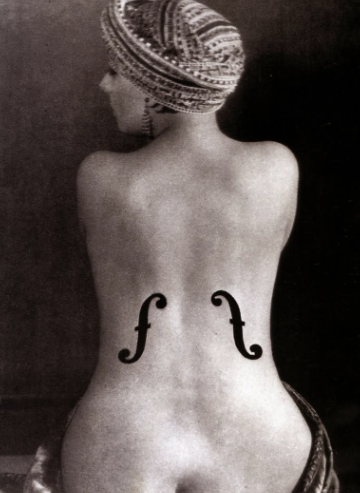

I remember learning too, at a similar age, how challenging having a career as a professional musician or other artist would be. I became aware in my late teens and early 20s that musicians had to work much harder at their talent in order to earn a living, relative to other professionals. I realised that you could get away with being an “average” manager, an “okay” banker, a “reasonable” psychologist, (etc), and make a decent living, but you couldn’t get away with being an average, okay or reasonable musician, actor or painter. It seemed terribly unfair, and I was grateful that, though I enjoyed playing music, and wanted to play lots of instruments, that I was nowhere good enough to make money from it. My dad, who is a better pianist than I am, even now in his 80s, said “It can be your ‘Violon d’Ingres’” – your side interest. I have always loved that expression.

I never entertained the idea of studying music, not for a minute. But I was determined to play multiple instruments. After learning piano as a kid, I started cello aged 25, saxophone aged 35, and was so enthused that I created a list of “instruments to learn”, one a decade, up until I was 95. Ten years of each. The list included clarinet (including bass clarinet), oboe, classical guitar, harp, and the double bass. (Sometimes the drums made it onto the list but I realised I’d have a space issue).

By the time I was 45, I realised that I missed playing the cello. More significantly, I had met a woman at yoga, Amaryllis, who became a friend, and who was a decent cellist. She agreed to teach me. By then I had dropped the saxophone because I wasn’t progressing. All the teenage saxophonists in the village orchestra had zipped past my level, in the blink of an eye, and I only ever got given the easy parts to play. It was the right thing for the conductor to do, but in addition there were too many of us, and most of the time I ended up not playing for “musical balance” reasons.

So I dusted off my cello and started it up again. I realised that beginning to play a totally new instrument was not what I wanted to do. I just needed some variety in the instruments I played. I no longer had an aspiration to learn many instruments (or I realised how hard it was going to be). Having learned and played piano, cello and saxophone to various levels, I find them challenging enough, different enough, rich enough, and I know that they will keep me happy for whatever time I still have playing music.

Post-loss, where energy management has been my primary activity, I can monitor my mood and well-being by which instrument I want to play. The instruments represent a kind of barometer of my energetic levels.

Piano is my “go-to instrument” for being comforted and soothed. Piano is what I play with a mug of tea, a tisane, or a glass of wine. Piano is how I accompany myself when I want to sing. Piano is the only instrument I can play while also crying. And piano is the instrument I accompanied (and occasionally still accompany) my kids to, as they played flute, trumpet or oboe.

But there’s no crying possible while playing saxophone or cello. Saxophone and crying do not go together for obvious “embouchure” reasons. Snot and tears don’t do the instrument any good, and wet fingers get slippery. Saxophone also demands good lungs and lots of stamina. A lot of puff. A lot of energy. I play standing up and it’s harder than sitting down. For my level of skill, it’s much more active, effort-full, than playing the piano. It has fallen by the wayside during Coronavirus times – I have lost fitness and don’t have the lung capacity nor energy for playing it.

In terms of instrument technicality, cello has always been hardest for me. So beautiful. But so hard to play well (for me). Full body physicality. Strength (and lightness) in arms and hands and fingers and thumbs. Three clefs to master – bass, tenor and treble. Needing to find and create your in-tune notes. No casual sloppiness permitted. Nothing laid out for you as on a piano. I never found cello easy and became easily frustrated with how “off “I sounded despite practising.

But my oh my – if I could scoop all of my “amateur musical talent” across the three instruments into one, if I had to choose between playing three instruments “okay” or one instrument “well”, I would choose to play the cello at a much higher level. That rich, deep, dark chocolate sound. The vibrating of the soul. The reaching into strum the heart’s strings. Of the three, it’s the one I wish I could really master.

It’s also the instrument that is more laden with emotion for me. I started cello for the second time when I was in my late 40s, when my brother Edward was first diagnosed with a Glioblastoma brain tumour. He was operated on, recovered well enough, then it came back 18 months or so later. When he became quite ill, I was still playing some cello, progressing a little, playing around the edges of going to visit him at home, in hospital, in the hospice.

After Edward died, on the 10th January 2016 (the same day as David Bowie died), I carried on playing. I was working towards my Grade 6 exam and I wanted to pass it. The kids were also doing some music exams – Megan had flute, Ben had trumpet, and Julia had oboe. They were getting to the age when they thought they shouldn’t be doing music exams “outside the French music or school system”, and I thought that if I did an exam too it might cajole them on a bit.

I sat my grade 6 cello exam on 22nd May 2016, on what would have been Edward’s 47th birthday. In the weeks coming up to the exam, when I knew the exam would fall on Ed’s birthday, I determined to play “for him”. I knew my level was touch-and-go. I could as easily pass as fail the exam. Some parts of all pieces were challenging, and my arpeggios were not solid or confident enough.

I dedicated the exam, and one piece in particular, to him. My dad accompanied me, which felt right and proper. I was teary. Really quite fragile. Cello for me needs body and emotional control. Trembly fingers and sweaty palms are not recommended.

I passed my exam – just. But that was the last time I played my cello. I “regressed”, reverted, to my piano. My steady, reliable, “fall-back” instrument. For comfort and ease. Predictable and soothing. And so it has been for the last few years. I have played some saxophone and enjoyed it but Coronavirus got in the way of lessons and orchestra, so I didn’t rebuild enough skill.

Amaryllis, my friend/cello teacher, played her cello at Julia’s funeral. The first movement from Bach’s solo cello suite number 2. A terribly mournful and “minor” piece. Sadly perfect for the moment. Perfectly sad.

Of course I have not picked up my cello in the illness, dying, death, struggling, grieving years. It’s too much. Too much energy, too close to my heart. Unlike the saxophone or piano, there’s a holding of sorts with the cello. At risk of sounding like a “proper” musician, I become “one” with the cello, even at my basic level. Arms encircling. When sitting down, sort of the same size. An embracing. So no. I hadn’t played. I had wanted to. I had really wanted to, but the energy required didn’t match the wanting.

Until last week. The cello got dusted off yet again, tuned up, and I have played four or five times since. It feels lovely, even if I am back to a basic level. It’s hard on my arms and thumbs, hands and fingers. Reading the notes and finding them is not a problem – that much I know. But it’s emotional work. I am close to tears every time I play. So much is evoked.

I don’t yet dare go and have a look at “Edward’s piece”. Instead I picked up some studies, some exercises, and then a “golden oldie” that I have been playing on and off for decades. A piece by a certain Arnold Trowell. I don’t know how I came across the music but I have had it since my “first go around” with cello. I have never worked at it with a teacher, just only ever picked it up with my dad playing the piano part. Usually at Christmas and following a glass or two of wine. I always played it sloppily, but it’s a lovely little piece. We always wondered who “Arnold Trowell” was, a composer whose name seemed so unknown for the enjoyment he’d engendered in us. (Turns out he’s a New Zealander, born in 1887 and died in 1966, the year before I was born).

So the cello piece was on the music stand when Medjool came over this weekend. I’d left the piano part on the piano because it’s also delightful to play (and easier for me, relative to the cello part). Medjool picked it up and started to play it. He’s heard me play piano, and we’ve had fun at some piano duets in the past. He’s even heard me play saxophone from a distance. But we haven’t done much together music-wise because of time, and because we come at it from such different angles. I can only play music with the notes on a page in front of me. I cannot improvise and I cannot play just from chords as both Megan and Julia can. It’s such a different talent. Medjool has played piano with music in the past but became disenchanted with it, and shifted to improvisation years ago which he does very well. But only very rarely do we play music together.

So I suggested we “have a go” – me on cello and him on piano. It was lovely, wrong notes and all. Truly moving. And as I put my cello back in its case, I felt a deep knowing, sad and soothing in equal measure, that this precious man is, at some stage, going to take over the “piano accompanying reins” from my dad. Medjool left with the piano score, determined to get it up a notch before we next see one another. I will try to do the same with the cello part.

Long may I still be able to play cello and piano and maybe saxophone with my dad. Long may Ben and Megan play their trumpet and flute and sing with their granddad. Long may Medjool and I make very amateur but fun music together.

And long may all five of us nurture our “Violons d’Ingres”.