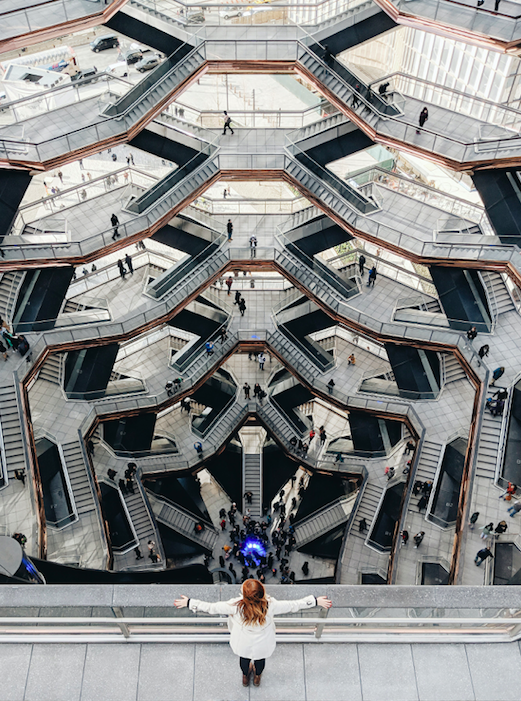

Photo by Juliana Malta on Unsplash

30 August 2020

I have just written this for my 53rd piece of weekly writing for Soaring Spirits International, which means I have been writing on their site for a year. My gentlest year in five years.

I wanted so much to be able to write that there had not been another death in my life, in my close entourage, by which I mean, the death of a person I love, affecting me strongly; or the death of someone close to a person close to me, affecting them strongly. For a split second I thought, “By golly – no deaths for a year”, but that’s because I wasn’t thinking straight. And then I remembered. Medjool’s mum died in March. Not of the Coronavirus – I feel compelled to clarify that. But of a fast-moving cancer diagnosed barely 10 weeks before her final breath. There might be some comfort in that. Or not. “She was in her 80s, after all”. And yet, absolutely an enormously gaping hole left behind by a much-loved mother, granny and friend, of central importance in many people’s lives. I didn’t know her long enough to sense the fullness of that gaping hole for myself, but I see it in Medjool’s life, the consequences of all of the “big and little changes” rippling through his life daily, and that of her immediate family. Mental adjustments having to be made frequently as he re-re-re-re-remembers that she is not there. Not here. And, I knew her long enough to love her and to be loved by her. I miss her too. She reminded me of my Granny May with her sharp mind, her warm and welcoming spirit, and especially her ability to engage with people of all generations and backgrounds.

So no – I haven’t had a run of no deaths these past 12 months. Instead I have had yet another year exploring the intersection of love and life and death. That messy, intricate, entangled space where, on a daily basis, moment-by-moment choices have to be made about whether to live, or not live; live fully and deeply, or live shallowly; embrace fear and unknowns with courage, or flee from the uncertainty of everything; engage or disengage with life; be real or fake in how to show up with the light and dark and shattered and fragmented parts of oneself; with hopes and dreams with their underbelly of sadness and trauma.

A couple of days ago I participated in a 90-minute discussion on “Hope after a suicide loss”. One of the questions I was asked was, “what would you say to people who have been affected by someone’s death by suicide?” My answer related more to living with loss(es) than specifically loss after suicide – I could probably have come up with this list before Julia died by suicide, after “just” the other three deaths. So it’s not so much about suicide. I like my list and it keeps me more or less functioning. My points were:

- It’s not your fault. Really. Truly. Even if people’s clunky questions might make you feel it is.

- Find a community that supports and represents you – even if it’s just one or two people. My widowed community is no longer enough for me, though it’s a piece of my support network. Communities of people who have lost a child are not enough – fuck it – they usually have their spouses to comfort them, to walk alongside them, to lean on. Communities of people who have lost someone to suicide are not enough. But I have found two people, two brave souls, who have lost a spouse and a child – or more, in both cases. Just knowing they are there, that they still love life and live and love fully, is all I need. I don’t need to hang out with them. I just need to know they are there, that they exist. Sort of like lighthouses continuing to project beacons of light. Tom and Nancy. You are my lighthouses. It’s the biggest compliment I can give you.

- Do it your way. Be kind to yourself. Be with your emotions: joy, deep sadness, all of it – without judgement. Please don’t add extra pain to your pain.

- Hold boundaries – you don’t need to take on others’ pain, whether related to your losses or their losses. It’s okay to say, “Sorry – I’m not talking about it” to people when they ask for information or support about your losses, about their own fears, or a child in their life who they know is struggling. I get so many requests – “Please help me with my child/nephew/friend’s child”. I am polite and as helpful as I feel able to be in the moment, but otherwise I don’t go there. I don’t get involved. I do not bend over backwards. I cannot. Not yet. Maybe one day. Maybe never.

- I don’t think the world needs another loss. This is my response to people who (still) exclaim, “How on earth do you carry on?” And I sometimes mention a handful of the gazillion things I love about being alive. My dying at this juncture doesn’t solve much for anyone. I truly believe that I am more useful to many people alive, and long may that be so.

Yes, living is messy. Loving is messy. Death and dying is messy. Grieving is messy. And the messiness allows for creativity and options and taking time to figure things out and trial and error. Making choices. Moment-by-moment choices as to whether or not to live fully until you inevitably die, or to choose to die while you are still living.

On almost a weekly basis I find myself face-to-face with end-of-life residents of all ages at the hospice who are living fully till they die – who mostly would like to carry on living.

And on almost a weekly basis I find myself face-to-face with grievers who say, “I just want to join him/her”. It’s okay to think and feel like that from time to time, but not for too long, please.

Another death serves no-one. Not right now. Not yet. In time. For sure, in time. But not quite now.

Life is still okay. Life is good enough. Life is more than good enough. Life hurts hard, really hard, and I still love it. Despite it all. Despite everything.

I want to share one of my favourite grief – or rather, life – poems here.

The Thing Is – by Ellen Bass

to love life, to love it even

when you have no stomach for it

and everything you’ve held dear

crumbles like burnt paper in your hands,

your throat filled with the silt of it.

When grief sits with you, its tropical heat

thickening the air, heavy as water

more fit for gills than lungs;

when grief weights you down like your own flesh

only more of it, an obesity of grief,

you think, How can a body withstand this?

Then you hold life like a face

between your palms, a plain face,

no charming smile, no violet eyes,

and you say, yes, I will take you

I will love you, again.